Pity the poor 21st-century writer who became a Josephine Tey fan in her/his formative years. Vanity Fair contributor Francis Wheen explains why in this excellent story from September 2015:

Pity the poor 21st-century writer who became a Josephine Tey fan in her/his formative years. Vanity Fair contributor Francis Wheen explains why in this excellent story from September 2015:

Decades After Her Death, Mystery Still Surrounds Crime Novelist Josephine Tey

Perfect! I wrote sonnets (and other poetry), and I wrote plays. I avidly read horse stories, magic and fantasy, international adventure, and science. I played basketball, softball, and field hockey; I was a champion broad-jumper and short-distance runner. Like Josephine Tey, I fiercely resisted any pressure to narrow my focus. I still do.

Francis Wheen writes:

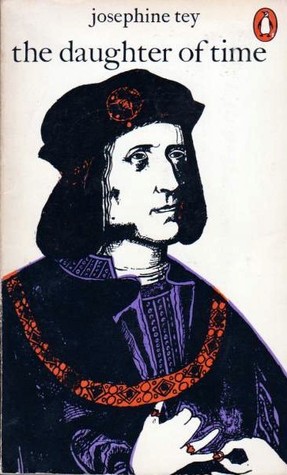

Francis Wheen writes:[Tey’s] disdain for formulaic fiction is confirmed in the opening chapter of The Daughter of Time (1951). In a hospital recuperating from a broken leg, Detective Inspector Alan Grant despairs of the books on his bedside table, among them a writing-by-numbers mystery called The Case of the Missing Tin-Opener. “Did no one, any more, no one in all this wide world, change their record now and then?” he wonders despairingly.

Was everyone nowadays thirled [enslaved] to a formula? Authors today wrote so much to a pattern that their public expected it. The public talked about “a new Silas Weekley” or “a new Lavinia Fitch” exactly as they talked about “a new brick” or “a new hairbrush.” They never said “a new book by” whoever it might be. Their interest was not in the book but in its newness. They knew quite well what the book would be like.

Still true today (are you listening, James Patterson and Lee Child?), but this is not a charge that could ever be made against Josephine Tey. In The Franchise Affair (1948) she can’t even be bothered to include the obligatory murder: all we have is a teenage girl who claims that two women kidnapped her for no apparent reason, and we know almost from the outset that she is lying.

What a 21st-century writer must contend with, unlike Tey, is a flooded book-publishing market in a culture that’s shifted its focus to television, film, audio, and other content-delivery modes. Commercial publishers rarely consider new authors at all these days, even in genre fiction, but they shrink in horror from a genre fiction book that’s not part of a series. It’s all about marketing. The looming mystery in the publishing world is how to forge that crucial (and preferably lasting) connection between books and readers. And among the core assumptions is that readers’ interest is “not in the book but in its newness” — the same author writing the same kind of story as last time, but with some different characters and a twist in the plot.

What a 21st-century writer must contend with, unlike Tey, is a flooded book-publishing market in a culture that’s shifted its focus to television, film, audio, and other content-delivery modes. Commercial publishers rarely consider new authors at all these days, even in genre fiction, but they shrink in horror from a genre fiction book that’s not part of a series. It’s all about marketing. The looming mystery in the publishing world is how to forge that crucial (and preferably lasting) connection between books and readers. And among the core assumptions is that readers’ interest is “not in the book but in its newness” — the same author writing the same kind of story as last time, but with some different characters and a twist in the plot.

Can anyone nowadays work successfully in both fiction and playwriting? Or does marketing pressure oblige authors to pick one path and stick with it? Is this the same question museums answered decades ago when “cabinets of curiosities” morphed into organized sets of collections? Is it a question that’s currently shackling bright young people to a professional specialty as early as middle school?

As for Josephine Tey, reading Francis Wheen’s inquiry reignited my desire to see a play by Gordon Daviot. Until then, I’m looking forward to rereading Tey’s mystery novels. I’m also cautiously curious about Nicola Upson’s series in which Josephine Tey is a character . . . and the biography that was still just a gleam on the horizon when Vanity Fair published this fascinating account of that vanishing golden-age renaissance woman, Josephine Tey AKA Gordon Daviot AKA Elizabeth MacKintosh.