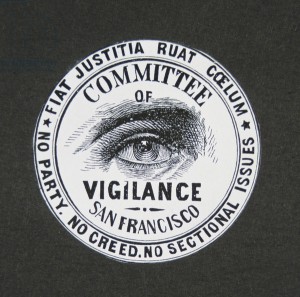

Any time a group of citizens snatches the political reins out of their government’s hands, they’re bound to offer a reason. As the United States of America’s founders put it in their Declaration of Independence, “A decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.” When Sam Brannan and his comrades pulled a coup d’etat 160 years ago, in a small but burgeoning city in the nation’s newest state, their recruits signed this declaration:

Whereas, it has become apparent to the citizens of San Francisco that there is no security for life and property, under the laws as now administered, since by the association together of bad characters, our ballot boxes have been stolen, our elections nullified, our dearest rights violated, and no other method left to manifest the will of the people,

Whereas, it has become apparent to the citizens of San Francisco that there is no security for life and property, under the laws as now administered, since by the association together of bad characters, our ballot boxes have been stolen, our elections nullified, our dearest rights violated, and no other method left to manifest the will of the people,

Therefore, the citizens whose names are herewith attached do unite themselves into an association for maintenance of the peace and good order of society.

The name and style of this association shall be the Committee of Vigilance, fo r the protection of the ballot box, the lives, liberty, and property of the citizens and residents of the city of San Francisco.

r the protection of the ballot box, the lives, liberty, and property of the citizens and residents of the city of San Francisco.

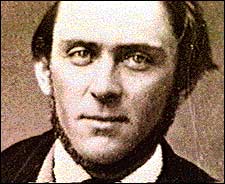

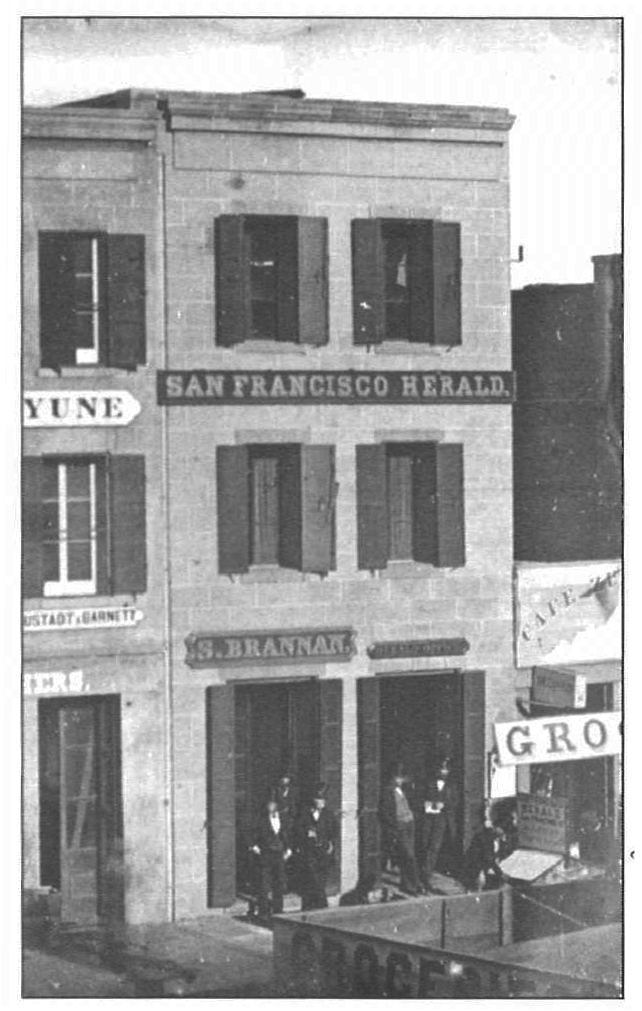

Samuel Brannan was a master of both spin and revolution. Seven years earlier he’d launched the Gold Rush by running down Montgomery Street shouting “Gold! Gold at the American River!” Brannan wasn’t a miner; he was an entrepreneur who’d bought up every pick and shovel in town. He’d already lost his race with Brigham Young to establish the new Mormon headquarters in San Francisco, as well as his race with the U.S. Navy to take California from Mexico. But he succeeded in goosing the sleepy little port of Yerba Buena into a Wild West free-for-all. In the process, along with creating San Francisco’s first monopoly, Sam Brannan printed the city’s first newspaper, milled its first flour, preached its first sermon, opened its first school, and became its first millionaire.

Men (and a few women) flocked in from everywhere seeking gold, adventure, and/or a fresh start. In California you could be whoever you said you were. If Sheriff David Scannell previously ran the Osceola Gambling Saloon, if Judge Edward McGowan’s first job was spinning a roulette wheel, who cared? Hungarian Count Agostin Haraszthy morphed into an American colonel, the head of the first U.S. Mint on the West Coast, and the father of modern California winemaking. Charles Cora, from Genoa by way of New Orleans, openly made his living as a gambler. His beautiful mistress–Clara Belle Ryan, a Baltimore runaway–became Arabella “Belle” Cora, madam of the city’s finest parlour house.

By 1851, Sam Brannan had carved himself a solid foothold as a merchant. Ironically, the anarchy that had enabled his rise to prosperity now threatened it. So he rallied his friends and formed San Francisco’s first Committee of Vigilance. Clamping down on lawlessness by hanging a few miscreants and scaring off many more not only protected their wealth but buffed their public image. Instead of looking like greedy entrepreneurs, Brannan and his fellows could look like civic heroes.

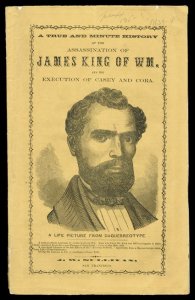

One of the city’s bankers was James King, who’d tacked “of William” onto his name back in Georgetown. He’d left behind his black-sheep younger brother Tom to join his admired older brother Henry, who was off charting the California wilderness with the bold but feckless explorer John Charles Fremont. To James King’s chagrin, Henry failed to meet his arriving ship, or to return to San Francisco at all. (Diaries would later disclose that he’d starved to death and been eaten by his lost comrades.) However, Tom soon followed his brothers West.

One of the city’s bankers was James King, who’d tacked “of William” onto his name back in Georgetown. He’d left behind his black-sheep younger brother Tom to join his admired older brother Henry, who was off charting the California wilderness with the bold but feckless explorer John Charles Fremont. To James King’s chagrin, Henry failed to meet his arriving ship, or to return to San Francisco at all. (Diaries would later disclose that he’d starved to death and been eaten by his lost comrades.) However, Tom soon followed his brothers West.

James King supported his wife and six children as part of the Montgomery Street financial crowd until the crash of February 1855. Broke and betrayed, he railed against the “too big to fail” corporations that had ruined him. In October he expanded his vendetta by launching the San Francisco Evening Bulletin, tackling vice and corruption citywide.

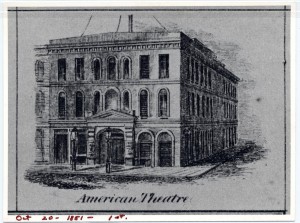

A month later, Charles and Belle Cora took their usual dress-circle seats at the American Theatre on Sansome Street. In front of them sat new U.S. Marshal William Richardson and his bride. Mrs. Richardson complained that a rude fellow in the pit was staring at her. When the marshal rebuked the offender, he answered that his eyes were on Belle Cora.  Richardson ordered the theatre manager to evict the soiled dove and her partner. The manager just laughed.

Richardson ordered the theatre manager to evict the soiled dove and her partner. The manager just laughed.

For the next two days Marshal Richardson stalked Charles Cora from bar to bar: drinking, threatening, and reconciling. Business in the city was a high-stakes gamble; many deals were sealed after hours, and many men carried weapons. Tension between the Tammany (Northern) and Chivalry (Southern) factions sometimes led to a duel. Richardson ambushed Cora, who narrowly escaped. The following night, when Richardson reached for his pistol, Cora shot him dead.

That was the break James King of William had been waiting for.

“One of the most cold-blooded assassinations . . . committed in our midst, and the same old song is being sung by the San Francisco press. ‘The prisoner must have a fair and impartial trial’ . . . I can see but one course for this community to pursue, and that is to take the administration of justice in their own hands.” So declared the Evening Bulletin.

That was the break Sam Brannan had been waiting for.

For what happened next, stay tuned for another episode in the remarkable yet true story told in my play and soon-to-be book After the Gold Rush.