by CJ Verburg

Rosa Mutabilis (Chinensis): one of my favorite flowers, from the SF Botanical Garden’s wonderful plant shop. Yesterday, after weeks, two green teardrops swelled into tight yellow buds. This morning I woke to these pale yellow flowers. Over the course of today they’ll blush toward peach, then turn sunset-pale pink. By tomorrow they’ll be a deep, vivid cerise.

In celebration, I made Ceylon tea in one of my favorite mugs, one that Edward Gorey designed to celebrate a technological advance in ceramics which delighted him. Heat sensitivity! A longtime master of secrets, suspense, and revelations, suddenly he could create a 2-stage object whose illustration (a lady enjoying tea on her recamier, framed by a black curtain) changed with the addition of hot liquid (the curtain vanishes to reveal a yegg snatching a statuette from her side table).

(a lady enjoying tea on her recamier, framed by a black curtain) changed with the addition of hot liquid (the curtain vanishes to reveal a yegg snatching a statuette from her side table).

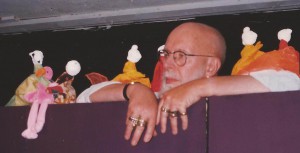

Theatrical magic! In the years we staged plays together on Cape Cod, a reliable offstage drama was the annual changing of the seasons. Every fall the green leaves of summer turned red, yellow, and brown and dropped off the trees, leaving behind a bleak landscape of vegetation so relentlessly taupe, and lacy branches so fragile, that one marveled at their ability to produce that vanished profusion of life.

It was Massachusetts’ frigid winters that dispatched me to California after Edward died. Every year I’d told myself: If it doesn’t get any colder than this, I’ll be OK. And then it did. Almost as stifling as the cold, though, was the loss of color. I cannot agree with the snippet of Shakespeare in this morning’s e-mail from the Globe Theatre in London:

‘At Christmas I no more desire a rose

Than wish a snow in May’s new-fangled shows,

But like of each thing that in season grows.’

Love’s Labour’s Lost (Act I, scene 1)

Not me. I always yearned for roses!

Likewise, I put up a fierce and furious resistance when Edward was felled by a heart attack in April 2000. Not that I thought I had any leverage with Fate; only I was absolutely 100% not willing for him to die. I sat by his hospital bed; I held his hand, invaded by needles and tubes. I talked to him, read to him, begged him to rejoin us.

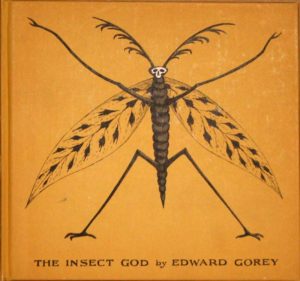

‘O feelings of horror, resentment, and pity

For things, which so seldom turn out for the best . . .’

The Insect God

Of the many aftershocks that followed Edward’s death, for me the most dreadful and unexpected was the co-optation of his work by its new owners, who goosed his unique style into a lucrative brand. That shift was already happening, of course — sales and royalties from his books and drawings were what paid Edward’s way. Death perhaps just speeds a transformation which is inevitable, or at least is the only alternative to being forgotten.

Of the many aftershocks that followed Edward’s death, for me the most dreadful and unexpected was the co-optation of his work by its new owners, who goosed his unique style into a lucrative brand. That shift was already happening, of course — sales and royalties from his books and drawings were what paid Edward’s way. Death perhaps just speeds a transformation which is inevitable, or at least is the only alternative to being forgotten.

Still, I’m ambivalent about last month’s publication of the first full Edward Gorey biography, Born to Be Posthumous. Author Mark Dery is a cultural critic who didn’t know the man about whom he is now the official expert. Many of Edward’s friends, leery of this posthumous invasion of privacy, chose not to participate, or to speak only of matters Edward himself had made public.

My reaction to the book, as one who can’t yet face reading more than snippets, mirrors Joan Acocella’s in The New Yorker:

Dery’s book is often fun, but that’s mostly because Gorey was fun. As for Dery, he should have been wiser. His discussions of Gorey’s work tend to be brief and shallow . . . Everything is goosed up—above all, what Dery regards as the dark, dark mystery of Gorey. Look at the book’s title, “Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey.” In what sense was Gorey born to be posthumous? To me, he seems to have done O.K.—found some happiness, created some admirable art—while still living. As regards eccentricity: funny how certain artists are that way.

Dery’s book is often fun, but that’s mostly because Gorey was fun. As for Dery, he should have been wiser. His discussions of Gorey’s work tend to be brief and shallow . . . Everything is goosed up—above all, what Dery regards as the dark, dark mystery of Gorey. Look at the book’s title, “Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey.” In what sense was Gorey born to be posthumous? To me, he seems to have done O.K.—found some happiness, created some admirable art—while still living. As regards eccentricity: funny how certain artists are that way.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/12/10/edward-goreys-enigmatic-world

Chacun a son gout. I can no more stop anyone from making whatever they wish of my late friend than I could stop the Great Bulldozer from flattening him. Or stop New England from turning cold when winter comes.

Yet it struck me as miraculous, then and now, that I could board a December flight from BOS to SFO and disembark into 360-degree color. And as much as I admired the stoicism with which Edward Gorey and most of our Cape friends endured those winters, I wish I could give him a cutting of my Rosa Mutabilis. He’d love watching its slow transformation, like the lady and the yegg.