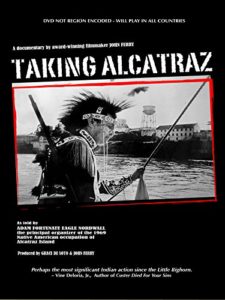

From November 20, 1969, to June 11, 1971, the island of Alcatraz was occupied by San Francisco Bay Area Indians who claimed it by right of discovery. (See Taking Alcatraz, Part 1.) When the California Historical Society hosted a showing of John Ferry and Grace De Soto’s film Taking Alcatraz on June 15, 2017, it also hosted a reunion. The second half of this collaboration between CHS and the New Museum Los Gatos (NUMU) was a panel discussion of occupiers and supporters. As hugs, handshakes, and a few teary eyes testified, some of them hadn’t seen each other in decades.

From November 20, 1969, to June 11, 1971, the island of Alcatraz was occupied by San Francisco Bay Area Indians who claimed it by right of discovery. (See Taking Alcatraz, Part 1.) When the California Historical Society hosted a showing of John Ferry and Grace De Soto’s film Taking Alcatraz on June 15, 2017, it also hosted a reunion. The second half of this collaboration between CHS and the New Museum Los Gatos (NUMU) was a panel discussion of occupiers and supporters. As hugs, handshakes, and a few teary eyes testified, some of them hadn’t seen each other in decades.

Stories emerged at CHS that were news to many of us in the overflow audience. Filmmakers Ferry and DeSoto and photographer Hartmann reconstructed the occupation, and the events that led up to it and followed it, in a series of interviews with spearhead Adam Fortunate Eagle and other participants. Hartmann’s extensive photographs are on view at NUMU (see also www.ilkahartmann.com). As described in my previous post, the occupation built from a small group of Sioux, to a larger multitribal group formed in response to a judge’s rejection of their original claim, to a 19-month live-in force of 79. That number fluctuated over time. Opponents claimed that commitment gradually dwindled. As the occupiers recalled it, reality intervened: commitment remained strong, but students had to go back to school, and other responsibilities called people away.

The U.S. government, mainly in the form of the Coast Guard, struggled from the start to remove the Indians from the island. Water, electricity, and phone service were cut off. So the occupiers lived in the guards’ quarters, where they had water and a generator. Food was ferried over by a crew of supporters, which grew along with popular awareness and support. Herb Caen ran regular updates; Creedence Clearwater Revival donated a boat. One skipper and panelist, Mary Crowley, was part of the original fleet that had transported the Indians to the island under cover of night, without lights.

Panelist Alan Harrison, a tribal member of the Robinson Rancheria, California “Pomo” Native American tribe on the banks of Clear Lake in Lake County, was one of the youngest occupiers at age eight or nine. His memories included playing with the toys donated by Mattel. Even younger was baby Wovoca Trudell, named for a Paiute religious leader, delivered on “liberated land” by Dr. Larry Brilliant when expectant mother Lou Trudell refused to leave.

Panelist Eloy Martinez, involved from the outset, recalled sailing over with the second party of occupiers and living on the island for seven months. He remained involved in civil rights, working with Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez, among others. Actress and activist Sacheen Littlefeather could only join the occupation on weekends. She’d been studying with Jay Silverheels, who played Tonto on The Lone Ranger TV series and ran the Indian Actors’ Studio.

Panelist Eloy Martinez, involved from the outset, recalled sailing over with the second party of occupiers and living on the island for seven months. He remained involved in civil rights, working with Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez, among others. Actress and activist Sacheen Littlefeather could only join the occupation on weekends. She’d been studying with Jay Silverheels, who played Tonto on The Lone Ranger TV series and ran the Indian Actors’ Studio.

“Everything about it felt right,” Mary Crowley summarized. “It was a peaceful, positive action. . . . A lot of good came from Alcatraz.”